Peptides are too small by themselves to elicit an immune response, so they must be crosslinked to an immunogenic carrier protein (e.g., KLH or BSA) for immunization. Peptides for antibody production (usually 4 to 20 amino acids) are simple and affordable to synthesize and conjugate in quantities sufficient for immunization. Peptides allow focused production of antibodies against point mutations or polymorphisms, post-translational modifications, and highly-conserved proteins (by specifically designing against the few variable regions). When they can be designed based on knowledge of the target protein structure and function (as with the Antigen Profiler System), peptide antigens offer the greatest control of antibody production for specificity and performance in particular assay applications. Given that whole proteins are more likely than peptides to present normal secondary and tertiary structure, they are more likely to elicit production of antibodies that bind certain epitopes that are present only in the native protein target, as is usually the case in ELISA and immunoprecipitation. The result is production by the animal host of a broad range of antibodies (a) that can be screened to select particular clones for different applications during monoclonal antibody development or (b) can be used as a polyclonal population (antiserum) to provide the broadest possible affinity and utility for multiple applications. Protein antigens are generally best when the goal is to elicit production of as many different antibody clones to detect as many different possible epitopes on the target protein. Gene-specific expression of recombinant proteins (or recombinant protein fragments) is often used to ensure that the purified protein antigen is precisely the one intended. Nearly any purified protein (>90% pure) can be used as an antigen for antibody production.

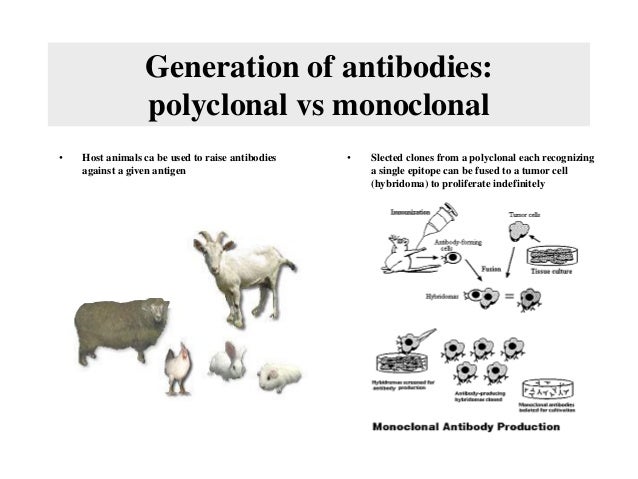

Larger animals yield more antiserum per bleed than smaller ones.īecause monoclonal antibody development yields cell lines that produce exactly one specific molecular form of antibody which can be maintained and cultured indefinitely, it is the best option for applications requiring consistent performance in quantitative detection, regardless of production batch.

These provide the opportunity to design assays to take advantage of host-specific secondary antibodies. Several different host species can be used for polyclonal antibody production, including rabbit, guinea pig, rat, mouse, goat, and chicken. The main disadvantages of polyclonal antibody production are that it yields only a limited amount of antibody (i.e., the duration of the immunization schedule), having variable consistency. A population of antibodies having greater specificity can be obtained by secondary purification (positive or negative) from the antiserum. They are far less expensive to produce than monoclonal antibodies and they generally have higher affinity and broader utility across assay methods. Polyclonal antibodies are nearly always the best choice for applications involving qualitative detection or purification, such as western blotting or immunoprecipitation. Crude serum usually contains several particular antibody clones against the injected antigen, as well as against other antigens to which the animal has been exposed in its environment. Polyclonal antibodies represent the total population of immunoglobulins produced by an animal in response to an antigen.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)